by Albert Nissman

Nissman, Albert (1983). Philosophical Antitheses: Mending the World; Staying the Course; Revising the Age of Triage, JBN Book Review: Judaica Book News, 13, pp.18-19, 42-46.

Dr. Albert Nissman is a Professor of Education, Graduate Division, Rider College

The following is excerpted from the complete review of the Israel Charny book – excerpted from a much longer review of the three books below. Charny comments in response that “Many fine reviews applauded the GENOCIDE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM (GEWS) presented in this book while ignoring the psycho-philosophical core issue of life and death, and the dialectic between them, that I believe is at the foundation of so much human experience and behavior – including human beings’ readiness to commit genocide. This was probably the best of the many reviews of the book.

How Can We Commit the Unthinkable? Genocide: The Human Cancer

Israel W. Charny

Westview Press and Hearst Books

To Mend the World – Foundations of Future Jewish Thought

Emil L. Fackenheim

Shocken Books

The Age of Triage – Fear and Hope in an Overcrowded World

Richard L. Rubenstein

Beacon Press

Introduction

Fackenheim pursues philosophically/historically his concern with restoring to wholeness the world that has been ruptured because of the Holocaust. Rubinstein avers that genocide and triage are grounded in the sociological/historical forces that are spawned by economics. Charny examines psychologically and psychiatrically the psyche – individually and collectively – and concludes that all “normal” people can become active genociders.

These three authors in three significant works examine man’s inhumanity to man from assorted but organically related disciplines. Of course, this fact tenders additional testimony to the truism that the Holocaust in particular and genocide in general are interdisciplinary studies which embrace the gamut from agriculture through zoology, and traverse the physical sciences, the social sciences, the arts and the humanities. There is an organic relationship between and among these disciplines and Holocaust/genocide studies must be pursued through all intellectual processes and areas. Of course, this is not to minimize or denigrate our need to view the Holocaust through our emotions as well.

Just as no human being can rightfully lay claim to being educated unless he has drunk from the wells of the various disciplines, no human being can lay claim to being sensitive, human, conscious, and educated, who has not grappled intellectually and emotionally with the Holocaust in all its ramifications, philosophical, historical, sociological, anthropological, financial, religious, theological, moral, affective, and scientific.

Dr. Israel Charny, an internationally known psychologist, is the Executive Director of the International Conference on the Holocaust and Genocide, and Co-Director of the Genocide Early Warning System Projects at the Henrietta Szold National Institute for Research in the Behavioral Sciences, Jerusalem. His present work represents eight years of research. It was the result, in part, of Charny’s belief that there is very little information available about the genesis of genocide. This book, a “dialectic of life and death,” revolves about two metaphors, cancer and electricity. Charny suggests that the clue to understanding genocide lies in understanding the alternating currents of the human psyche.

It seemed to me that through the veil of the everyday agonies of human beings, in our hurts and disillusionments and in our hurting of others, we should be able to learn something about man’s larger madness of destruction and genocide.

None of us are immune from the danger of possibly becoming mass killers, and none of us are entirely lacking in humanity and decency. Whatever it is that makes people monstrous destroyers is somehow potentially in all of us. The seeds of the cure, it seemed to me, were all potentially in all of us.

That is to say that in the basics the Germans were not that much different from the Jews. But the question remains: what makes normal people, good and creative, become genociders or their willing henchmen? Charny avers that “man’s genocidal destructiveness can be seen as a process to be studied, charted, and managed correctively.” He calls genocide “the cancer of man’s destructiveness.” It is the first metaphor of this book. It is his feeling that “nearly all ‘normal’ people are capable of being genociders, accomplices, or bystanders. In no way, however, is Charny’s work an apology for committing mass murder.

Charny explains and translates complex but incomplete research into understandable but perplexing units of comprehension. Genocidal tendencies cross all professional, educational, social, economic and national boundaries. All people are in danger of succumbing to authority. We must learn to recognize and control our violence.

To my mind, the most important psychological issue is whether a person has respect for human life and human experience, beginning with a deep feeling for the miracle of his or her own being, and then by extension, has respect for the integrity of the lives of others.

Genociders are typically like you and me; they have not been diagnosed abnormal by current clinical concepts which focus on how sane a person is and not on how human he is. “The Holocaust convincingly brings home the truth that genocide is a complex of forces that can be set off in virtually any society of normal human beings.”

Charny cites many paradoxes of human nature. Amidst all violence we deny violence. People kill in the name of God. People destroy in the name of life. People wage death to gain immortality.

Human beings are at one and the same time beautiful, generous, creative creatures and deadly killing genociders. He calls this the “hitherto intolerable contradiction.”

Charny finds an explanation for this dilemma. “The two immutable facts of life are life and death.” However, in an existential stance which I applaud, Charny writes, “Whether or not we are driven by deterministic forces, each of us must bear full responsibility for the choices we make whether or not to be destroyers.” He develops the two unchanging facts of the human condition ‘We are alive! And We are dying!’ into several permutations and combinations.

Being is the integration of living and dying; on the one hand, being alive and feeling alive; on the other hand, accepting one’s everyday limitations and “deaths” as well as the inevitability of one’s ultimate death.

Charny cites the “cancer of human experience”: not fighting hard enough for life; trying to live too much; veering toward destructiveness. Often, the impotent human being says in effect:

I’ll prove that I am not terrified of death [yours]. I’ll prove that I can control life and death. If I am powerful enough to bring about your death, then I can keep death from my own door.

So gaining and showing power is a source of gratification.

Charny’s second metaphor is electricity or nuclear human energy. It deals with positive forces and negative forces, the two complementary sides of human aggression. The positive forces leads us to love, to build, to create. The negative force leads us to attack, tear down, break down, pull away, and dismantle. All nature has the “counterpointing of opposite forces.” These contrapuntal forces release energy which “can be marshaled, channeled, gauged, and corrected.”

Excessive building or excessive tearing down of the positive forces or the negative forces is destabilizing. There needs to be a balance of love and hate. When there is an imbalance, there is an excess of love or hate, “There is a basic dialectic pull between healing and destroying.” There is a need to care for and love oneself; there is also a need to care for and love others. There, too, is a need to assert oneself – to be aggressive. Our levels of energy, the balance of our positive and negative forces, determine our choices of means and ends. Our power can be constructive or destructive. When we choose the destructive mode upon others, ultimately we also destroy ourselves.

Charny sees the crux of the human condition in our living toward death.

All of life’s flow is a continuity of ever-renewing creation moving toward inexorable death. These givens necessarily place these forces at the center of human experience and thinking.

An interpretation of Eros, the life force, and Thanatos, the destructive instinct, as Freud called them, is needed.

Various theories about man’s goodness abound: man is basically good; man is basically evil; man is basically neutral. It reminds me of the anthropologist who viewed man as nothing more than an alimentary canal with an aperture at either end. Through life experience this canal then picks up its cultural baggage and becomes a human being. Charny writes:

Life loving is not a constant, but a flow that bends and yields to life-destroying impulses when people are tired, threatened, seduced by power, or drawn by the promise of apparent immortality. There are many reasons, therefore, to conclude that all people have within them a fundamental potential for evil and that most people, including those who are otherwise “good” in everyday life, are capable of making dastardly choices. It is this truth of the naturalness of evil that is not accounted for in the optimistic conception of man as intrinsically good.

In the natural essence of his aliveness, man is inherently, powerfully drawn to both life building and life destroying.

Thus, each of us can be a genocider.

Good and bad are the two sides of naturalness. Charny quotes aptly from a Jewish legend: “Were it not for the existence of the Evil impulse, men would not build homes, they would not marry women, they would not sire children, and they would not engage in trade.”

Charny feels that man has the potential to gauge, regulate and channel his impulses; however, this potential has not been tapped. History is replete with misguided people who engaged in human destruction, thinking that they were advancing a righteous cause.

People tell themselves that destructiveness doesn’t “really” count because it is intended to be the forerunner of a greater good. That justification has been heard from the advocates of all kinds of destruction in human history. “Ours is a crusade for God’s glory.” (Kill the infidel!) “Ours is a revolution for equality and liberty” (Kill the artistocrat!) “Ours is a noble effort to improve the race” (Kill the non-Aryans!)

Charny feels that most people are basically alive and welcome their own aliveness and the aliveness of others. He feels that most destruction is not based on hate, but fear and uncertainty about the human condition. Returning to his metaphor of electricity, he thinks that people suffer from deep anxiety; they do not know how to gauge the extent of their power, but let it out all the way; they get drunk with power – overloading or short circuiting. They suffer power excesses and/or power insufficiencies.

Further, there is a lack of knowledge of choosing proper means that lead to our goals; people are not trained to choose life’s goals; they know little of relating means and ends; feelings and actions; they do not know the difference between inner experience and overt acting out of feelings. They need to learn how to monitor and pace the threat process.

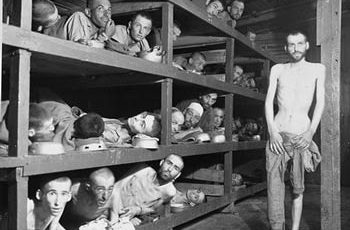

The Holocaust of the Jewish people in Europe spelled out irretrievably how fully man can disassociate himself from the humanity of his fellow human beings as he callously masses people for destruction as if they were no more than toys to serve his diabolical humor. The same situation exists in the holocausts that are taking place this very day here or there on the face of this blood-soaked earth. Could we be anything but terrified?

People need to differentiate between self-defense and illusion; they need to recognize the corruption of power and the process of scapegoating.

The mechanism of projection enables a person to attribute to others whatever one fears in oneself. Since the central fear in man’s experience is nonaliveness and death, that is the essence of what men are projecting onto others in one form or another form: “I will cast my fears of death onto you. I will claim for myself the life force you appear to possess.”

Some feel that one can turn the genocider away by not challenging his sadistic power, by turning the other cheek, by engaging in pacifism. (Paranthetically, it can be argued that such pacifism worked for Ghandi against England only because that country in inherently democratic and humane; his pacifism would never work against the Nazis or their ilk. They would just become more sadistic and genocidal).

Individual man is lonely and seeks groups for comfort. Charny writes:

Groups provide something of an antidote to the terror of facing life all alone. However, so beguiling is this opportunity, so captivating the group experience as a way of relieving untold terrors of aloneness, that many people try to bypass and do without the pain of being an individual.

Groups offer the individual identification, a feeling of solidarity. The provide names, insignia, pageantry, protocol and uniforms. Group members “caught up in a mass group frenzy” have abdicated their individuality, their powers to choose, and their responsibility. But everyone ultimately must be responsible for his choices and be ready to accept the consequences of his actions.

Whether genociders work as singles or groupies, they share a perception.

One important difference that did begin to emerge between the genociders and other people was that the killers seem to perceive other people as things which need to be arranged and ordered, rather than as humans.

Besides, all people are ready to label and categorize, engaging in[ the] triage [that Rubenstein writes about].

Charny believe that even the “foreign policy needs” of individuals have much in common with the foreign policy needs of nations. People and nations whose family life is unhappy, or who feel threatened, tend to engage in the destruction of others to bolster their feelings or to assuage their fears. “Breaking the grip of the notion that another nation and people are forever and totally evil is necessary if the door to the corrective processes that may save lives on both sides is to be opened.”

In our individual, married, collective, community, and national lives, we may define another person or people as not quite human. We recoil from the unfamiliar, the unknown. We project our fear of “weakness, vulnerability, and mortality onto those who are different and weaker than we are.” And of course, death is the ultimate vulnerability. Is this what propels “otherwise good people to murder, not in a moment of passion or self-defense, but in a cold-blooded, systematic extermination of helpless people?”

Bad or insane leaders and warlike cultures are not nearly the whole story.

…there is a “Hitler”in all of us, and Hitler himself was human too – so were Robespierre, Caligula, Cambodia’s Pol Pot and the many anonymous human beings in killer squads all over the world.

But one person cannot lead a genocide alone. He needs the complicity of all normal people who house a genocider within them. “…the people’s power rests on the availability to violence.” In committing genocide, followers and leaders feel less impotent, vulnerable, weak and mortal. Even in the U.S. where Constitutional checks and balances provide a saving grace, there is still danger in that “the U.S. tradition continues to be frontierlike and therefore tends to accept power and violence as everyday facts of life.”

Charny underscores the importance of choice. “You can throw off the chains of your background determination and exercise new choices (freedom) so as to be in charge of your life.” All of us make a choice to be perpetrators or spectators of genocide in some ways, a people’s tradition also predisposes them to choose to be victims. This does not mean in any way that the Jews, for instance made a conscious choice to become victims of the Holocaust, Charny explains.

The ability to choose is an active expression of the human’s gift of consciousness,and it is a man’s machinery for mapping and shaping his unfolding future. Unfortunately, most people have not been trained in the art of making choices.

The implication, of course, is that we all need to learn how to choose among being genociders, victims, or champions of life. Each of these roles has its attractions, and we must learn to choose among them. The art of making choices among enticing alternatives is probably the most important tool humans can use to find a solution to the dilemmas of good and evil.

Potential victims, to a certain extent, have a choice, too.

Genocides do not take place unless the killer gets away with it; stated otherwise, if the cost to the genocider outweighs the gains he achieves in acting out his superiority over a victim people, he will not commit genocide.

As Pogo of comic strip fame has said, “We have met the enemy and he is us!”

People fear winning because they then can also lose. They fear trying because then they can fail. That success implies perfection is a rationalization. “Self-hurting is not knowing how to be alive.”

The genocider, ridden with cancer of his humanity tries to destroy others to confirm his own potency. The victim, ridden with cancer of his humanity makes himself available to be subject to the power of others.

Traditionally, this has been the image of the Jew as victim. But the establishment of the state of Israel has changed and enhanced the image of the Jew as never before in history. “The psychoethical ideal [is] that all people should be neither oppressors nor victims.”

Charny believes that there is still room for reason and hope. He sees nonviolent aggression as healthful aggression and energy. He cites “strength of purpose,” will, self-expression, ability to fight for oneself..” as aspects of this healthful, aggressive energy. But people fear their own healthful aggression because they see so much genocide accrue from unchanneled aggression. But pacifism, too, has its drawbacks.

Granted, a pacifist makes an enormous contribution to his community because he never stops exploring any and all creative possibilities for making positive contact with the “Indians,” but when the arrows are about to fly, a good pacifist is a dead pacifist unless he shoots first and surest.

In short, healthy aggression helps us to assert ourselves, balancing good against evil.

People need to learn that “intimacy and conflict are inseparable in human life. This is true in the relationship between God and man. It is true in human relationships. These positive and negative forces operate in the ‘foreign policies’ of people as well as in the foreign policies of nations.”

Charny waxes a big eloquent:

The human species needs to learn to trust aggression as the great miracle of human energy. We need to understand that peace and non-violence are best forged from a joyful and disciplined experiencing of our natural energy, not from escape from ourselves. Aggression is the power to be: it is the hum of life.

However, this is not a warrant to destroy each other!

Charny cites four basic strategies for reducing violence: encouraging nonviolent aggression; monitor aggression for excesses and insufficiencies; guard against projection and dehumanization; and stop escalation of conflicts. He believes that these four strategies can operate in our personal lives and in our national lives.

Together religion and education often teach blind adherence to tradition, conformity to social mores, and unquestioning obedience to authority, all of which open the door to violence. Ultimately, the goal of all education and religion should be to inspire and equip people to fight for life – for themselves and all people.

All human beings have the inherent right to be alive, feel alive, act alive, and to live out their lives in peace and to die of natural causes, not genocidal acts! But this important lesson must be taught! Education and religion have not resolved satisfactorily how to transmit this lesson affectively and honestly. Once this lesson is learned then people and nations can monitor themselves and be monitored.

Perhaps Charny’s most interesting and radical concepts is his Genocide Early Warning System (GEWS- with a soft “G” as he says in another source). Throughout the world, reports ranging from the denial of civil rights to the murder of specific groups proliferate. People read or hear these reports and then immediately forget. They are frustrated; they do not know if the reports are true and they resign themselves to impotence – there is nothing that they can do about a particular report. Reports of actual genocide generally do not have the same impact as other disasters of upheavals; they are not treated with the same intense sense of urgency or immediacy.

To date, the United Nations and Amnesty International have been the main sources of these reports. But the effects do not seem to be far-reaching enough.

At this point in its evolution, mankind is deeply limited in its readiness to experience and take action in response to genocidal disasters. Most events of genocide are marked by massive indifference, silence, and inactivity. Some isolated events are followed by a measure of concern, outcry and protest; but even these genocidal events that do trigger some degree of awareness and protest are rarely followed by any significant efforts to correct or limit the genocidal process by people who are not connected to the events by reason of kinship or geographical closeness.

The GEWS, thus, would provide a systematic way of tracking relevant data via computer technology to offset the present lethargy and apathy. It would help us spot patterns, disasters, and actual genocide in progress. It would help us determine whether a particular incident is an aberration of part of a consistent chronology. The kinds and intensities of each incident would be tracked. The key in the GEWS would be the systematic observations noted longitudinally, verification, and publicity worldwide.

Since World War II, there has been a mounting concern about genocide; however, there seems to have been minimal concerned actions via any kind of intervention. Besides its worth as a symbolic message of humanitarian import, GEWS would provide “a designated institution to monitor and report the terrible events that destroy so many human lives.” Although a GEWS would motivate some genociders to proceed in haste with their planned madness, GEWS would generally have the reverse effect.

A Genocide Early Warning System would announce to all of us that mankind was gaining a new awareness of the widespread tragedy of mass murder and was seeking to develop new processes to control and remove the terrible cancer.

According to Charny, GEWS would serve as a “human environment ombudsman.” It would identify new threats at their early stages, encourage governments to take preventive actions, help governments generate the political will to act, and supply a non-political forum for discussion between nations.

The GEWS concept contains three levels of data collection: assembling of facts and defining of patterns and sequences; tracking a wide range of human rights violations that fall short of genocide; and tracking a “broad spectrum of social indicators.” These indicators would include societal and cultural processes that tend toward genocide in the valuing of life in a given society; in a culture’s patterns of power distribution; in an ideology of genocide; in patterns of dehumanization; and in legitimation of genocide.

GEWS would, therefore, provide a system to collate worldwide computerized data, thereby displacing or enhancing the haphazard collection systems now in operation. Authorized reports of extermination would be disseminated quickly and accurately worldwide and would influence public opinion. Predictability of genocidal events would become more valid and reliable.

Charny is aware that GEWS is not a panacea. He writes:

Although it is essential that we be aware of the past, there I nothing that says that historical awareness and heartfelt memorializing alone will correct man’s ways. There is little hope of ending genocide until we truly learn to understand the sequences and processes that lead to genocide.

In the final analysis, man must learn to understand “the basic conditions of being alive, staying alive, and feeling alive.” He must learn to understand the positive force and the destructive force inherent in these conditions.

In the final analysis, if a Genocide Early Warning System someday serves “only” to save several thousand potential victims by enabling them to flee the clutches of a genocider headed toward their homes, the effort and cost of building such an early warning system will have been justified.

Detailed appendices round out the book: a flow chart which shows how normal life processes can lead to genocidal destructiveness; the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” which bears constant re-reading and is blatantly violated every day somewhere in the world; and the United Nations Convention on Genocide which also bears re-reading to jar our consciousness. There is also a hefty supply of chapter notes, a useful index, and a selected bibliography.